Pharma is cool

As I've mentioned in the past, I entered college with a disparate array of aspirations. One of these goals was to attend medical school. I'm not really sure why I found this attractive--perhaps it's because my parents are both physicians with my brother in medical school.

Regardless, I decided to complete the pre-med requirements amidst my three majors in ECE, Math, and CS. Now, I know that seems excessive, but the preserved ability to attend medical school gave both my parents and myself a sense of assurance. Why? Well, building something technically sophisticated like a new compiler or a hardware accelerator is cool. As I've learned, building something that makes money often doesn't need to be cool but frequently requires providing some economic or emotional utility (consultants used to be able to charge lots of money before Palantir existed to tell businesses this fact in case they forgot). Moreover, building something that dramatically improves human health and society might not be cool nor make money. However, my childhood dream of building a robot surgeon seems to be all three of those things (for which an MD might be a pre-requisite).

Another product that seems to lie in the nexus of this loosely-defined venn diagram are pharmaceutical drugs. Pharma scientists spend a lot of time and effort to formulate, research, and produce chemical or biological substances that ameliorate bodily ailments and address the most foundational issue that of our biological species: human fragility. Roughly 2% of the US GDP is spent on purely pharmaceuticals (whereas healthcare is 18%). From an onlooker's perspective, this number might suggest that the number of Scrooge McDucks among pharma executives is proportionally higher than other industries.

Yet, the state and federal government cover roughly 60% of the sticker price for drugs. Accordingly, the drug industry is far from a free market; the government can theoretically dictate the price it pays.

THE Customer vs A Customer

I've been contemplating this pseudo single-buyer effect over the past two weeks, in large part because of the proposed MFN agreement between pharma companies and the US government. More pointedly, I've been wondering if a whale-buyer in a price-regulated market yields better end-results for individual drug consumers.

On one hand, the large revenue contribution of the US government should yield price-bargaining power. On the other, the US government is also often a dream customer because of their incredulous price-insensitivity even post-DOGE blip (the US military just paid $6B for Slack and a CRM).

Although one is meant to heal while the other is meant to kill, I've noticed a perplexing similarity between defense contractors and pharmaceutical companies. For both, there is a looming singularity in its customer-base: THE US Government. Additionally, both industries are effectively oligopolies in talent, scale, and distribution. And just like weapons, the eye-watering prices for pharma serves as a federal handshake incentive to innovate and engineer: build something new and you will be rewarded.

Now, does this work better than a simple free market? It's hard to say. Northrop charging over a $2b dollars per single B-2 plane feels inefficient. But maybe not! Maybe the seats fully recline and are really really comfy, so the cost is justified.

One fact that supports the inefficiency hypothesis is that pharma drugs seem to have an inverted elasticity curve: drugs that are more in-demand seem to be less expensive. One example of this phenomenon is Ozempic. Ozempic is perhaps the most popular drug in the US right now. Troves of non-diabetic people are using Wegovy or alternative GLP-1s to lose weight.

One might expect that this large demand-pool for a single (and somewhat elective) drug would instigate a price surge for consumers. However, what we see in the American healthcare system is quite the opposite. The popularity of GLP-1s actually renders price depression thanks to TrumpRX (which by the way, is hilariously vibe-coded to look like a womens designer brand). Prices have been cut by up to 90% in the US.

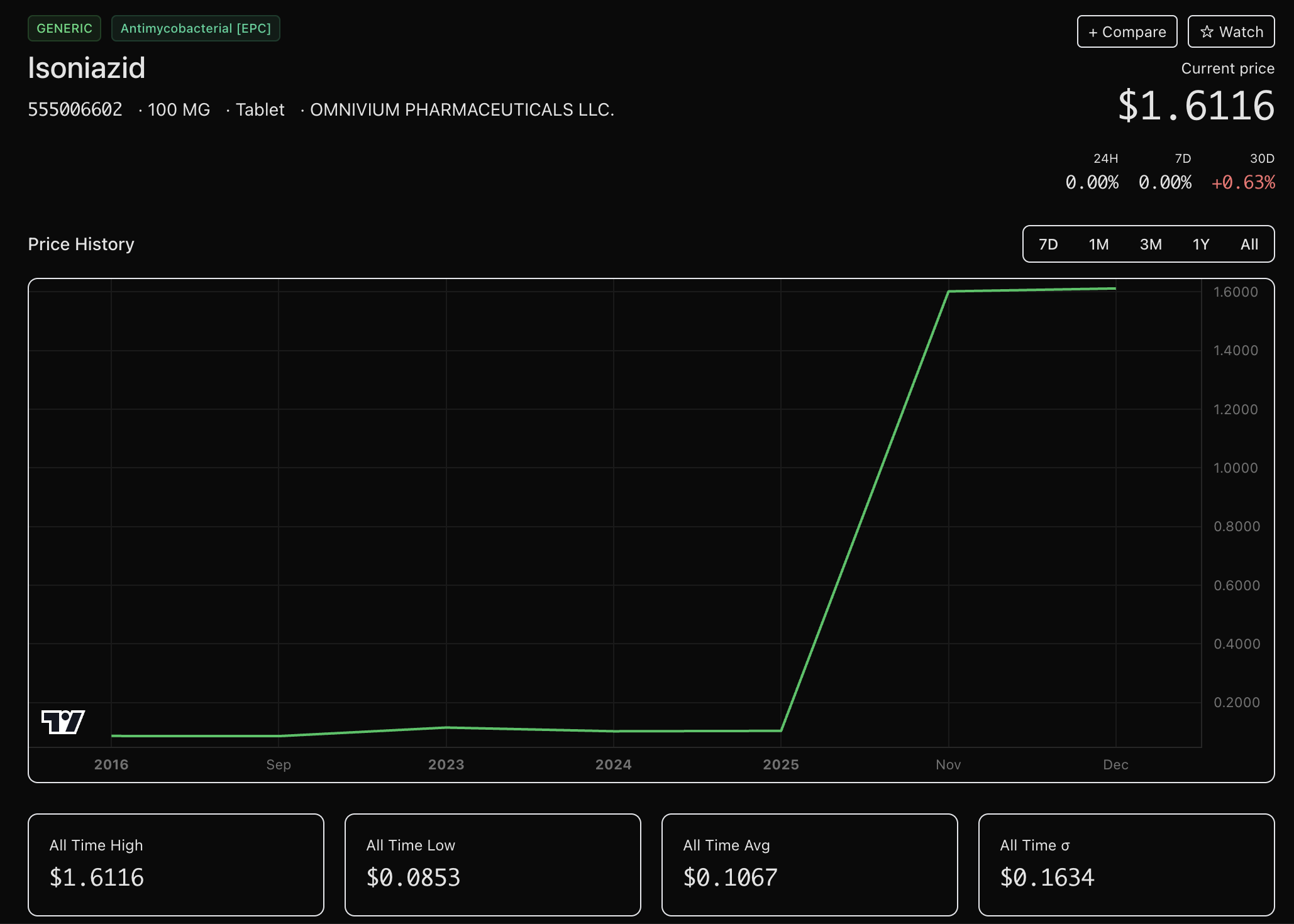

Obviously I have not conducted extensive research on drug prices in the US. However, the GLP-1 price curve is a stark juxtaposition to, say, isoniazid--an aromatic pyridine ring with an acyl hydrazide group used to treat Tuberculosis. After scraping the NADC data for the past 10 years, Isoniazid, along with many other important drugs, have exploded in prices by in some cases 1000% over the past few years. Now, I don't know enough beyond biochem to understand what how this functional group interacts with TB bacteria. But what I do know is that it is an essential drug for treating TB which can be life-threatening. But because there are only ~10k TB cases each year (compared to 30M GLP-1 patients), TrumpRX seems unconcerned with reducing their costs. To Dr. Oz and RFK, a drug that keeps moms skinny might be more important to America than a drug that keeps TB patients alive. It will certainly save the US more money through preventative care.

To some degree, these specialty drugs that are very important to a small subset of US patients remind me of the Northrop B-2. Because they are niche low volume products, high prices are almost necessary to incentivize the R&D costs to create them. Again, I am not a pharma expert, but the volatility of drug prices is fascinating.

Hedging Prices

Now, I know what you're thinking: two blogs about niche hedging vehicles in a row? I thought this was a blog about software and AI engineering. What can I say, I'm evidently impressionable to all those Kalshi commercials and Polymarket grocery stores.

Well, imagine I was a college student taking a lot of hard classes, I'll probably need to cram a ton of studying in a short duration for finals. To get through all that material in a week, I might want to take Adderall. But I don't have a prescription, so I'll need to buy it from the fifth-year who sits by the "American History" section in the library. However, I'm not the only one with finals, so lots of other college kids will be vying for study-drugs. If that fifth-year has learned anything in his once-a-week online econ classes, he might intuit that he can raise his prices before finals. Yet, if I can anticipate this likelihood, I suppose there are two logical choices. 1. I can study well ahead of time for all my classes so I'm prepared for my finals early and won't need to cram. Or 2. I can negotiate my adderall price ahead well ahead of time so I won't need to pay those inflated prices.

In the second scenario, I might buy the Adderall in advance, but that would require paying now for something I need later. I could also pay a small amount today for the right or the obligation to buy the Adderall at a specific price near finals week with options or futures. Or I could engage in a binary contract1this used to be called a bet. where, say, I am paid $60 if Adderall prices rise above a specified limit, else I'll pay $40 to the opposing party. Any of these choices can hedge my exposure to Adderall prices.

There is some legislature in the US that prevents advanced purchasing of pharmaceuticals. Additionally, physical deliverability of drugs from financial derivatives is also likely prohibited. However, today's financial ecosystem supports contract indexing (perhaps against NADC data) and tokenizing (buying lots of life-saving drugs, locking it in an underground vault so nobody can use them, and issuing crypto tokens representing these drugs).

Regardless of how the price is determined, the prevailing way for retail to hedge exposure seems to be binary contracts on these prices. Enabling drug purchasers, insurance companies, and drug manufacturers to hedge financial exposure to drug prices seems to have more utility than hedging my emotional exposure to a football game. Accordingly, I would contend that perps or binaries on drug prices may have some real need. In a way, they bring free-market price-discovery to products people actually need (kind of like power / oil) rather than letting the government and pharma execs set the price (kind of like the Northrop B-12).

Goated Stuff

- I didn't have time to find relevant papers. However, I've linked here a scrappy visualization tool I threw together for NADC prices. Now imagine being able to actually trade this movement or indexes.